Google engineers try to read users minds

These days, Google seems to be doing everything, everywhere. It takes pictures of your house from outer space, copies rare Sanskrit books in India, charms its way onto Madison Avenue, picks fights with Hollywood and tries to undercut Microsoft's software dominance.

But at its core, Google remains a search engine. And its search pages, blue hyperlinks set against a bland, white background, have made it the most visited, most profitable and arguably the most powerful company on the Internet. Google is the homework helper, navigator and yellow pages for half a billion users, able to find the most improbable needles in the world's largest haystack of information in just the blink of an eye.

Yet however easy it is to wax poetic about the modern-day miracle of Google, the site is also among the world's biggest teases. Millions of times a day, users click away from Google, disappointed that they couldn't find the hotel, the recipe or the background of that hot guy. Google often finds what users want, but it doesn't always.

|

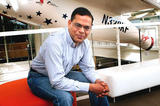

| Amit Singhal, a Google Fellow, pauses for breath at the company's Mountain View, California, headquarters on May 3. PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE |

Singhal is the master of what Google calls its "ranking algorithm" -- the formulas that decide which Web pages best answer each user's question. It is a key part of Google's inner sanctum, a department called "search quality" that the company treats like a state secret. Google rarely allows outsiders to visit the unit, and it has been cautious about allowing Singhal to speak with the news media about the magical, mathematical brew inside the millions of black boxes that power its search engine.

Google values Singhal and his team so highly for the most basic of competitive reasons. It believes that its ability to decrease the number of times it leaves searchers disappointed is crucial to fending off ever-fiercer attacks from the likes of Yahoo and Microsoft and preserving the tidy advertising gold mine that search represents.

"The fundamental value created by Google is the ranking," says John Battelle, the chief executive of Federated Media, a blog ad network, and author of The Search, a book about Google.

Online stores, he notes, find that a quarter to a half of their visitors, and most of their new customers, come from search engines. And media sites are discovering that many people are ignoring their home pages -- where ad rates are typically highest -- and using Google to jump to the specific pages they want.

"Google has become the life blood of the Internet," Battelle says. "You have to be in it."

Users, of course, don't see the science and the artistry that makes Google's black boxes hum, but the search-quality team makes about a half-dozen major and minor changes a week to the vast nest of mathematical formulas that power the search engine.

These formulas have grown better at reading the minds of users to interpret a very short query. Are the users looking for a job, a purchase, or a fact? The formulas can tell that people who type "apples" are likely to be thinking about fruit, while those who type "Apple" are mulling computers or iPods. They can even compensate for vaguely worded queries or outright mistakes.

`Give me what I want'

"Search over the last few years has moved from `Give me what I typed' to `Give me what I want,'" says Singhal, a 39-year-old native of India who joined Google in 2000 and is now a Google Fellow, the designation the company reserves for its elite engineers.

Google recently allowed a reporter from the New York Times to spend a day with Singhal and others in the search-quality team, observing some internal meetings and talking to several top engineers. There were many questions that Google wouldn't answer. But the engineers still explained more than they ever have before in the news media about how their search system works.

As Google constantly fine-tunes its search engine, one challenge it faces is sheer scale. It is now the most popular Web site in the world, offering its services in 112 languages, indexing tens of billions of Web pages and handling hundreds of millions of queries a day.

Even more daunting, many of those pages are shams created by hucksters trying to lure Web surfers to their sites filled with ads, pornography or financial scams. At the same time, users have come to expect that Google can sift through all that data and find what they are seeking, with just a few words as clues.

"Expectations are higher now," said Udi Manber, who oversees Google's entire search-quality group. "When search first started, if you searched for something and you found it, it was a miracle. Now, if you don't get exactly what you want in the first three results, something is wrong."

Google's approach to search reflects its unconventional management practices. It has hundreds of engineers, including leading experts lured from academia, loosely organized and working on projects that interest them. But when it comes to the search engine -- which has many thousands of interlocking equations -- it has to double-check the engineers' independent work with objective, quantitative rigor to ensure that new formulas don't do more harm than good.

As always, tweaking and quality control involve a balancing act. "You make a change, and it affects some queries positively and others negatively," Manber says. "You can't only launch things that are 100 percent positive." The epicenter of Google's frantic quest for perfect links is Building 43 in the heart of the company's headquarters here, known as the Googleplex.

At the top of a bright chartreuse staircase in Building 43 is the office that Singhal shares with three other top engineers. It is littered with plastic light sabers, foam swords and Nerf guns. A big white board near Singhal's desk is scrawled with graphs, queries and bits of multicolored, mathematical algorithms. Complaints from users about searches gone awry are also scrawled on the board.

Squashing bugs

Any of Google's 10,000 employees can use its "Buganizer" system to report a search problem, and about 100 times a day they do -- listing Singhal as the person responsible to squash them.

"Someone brings a query that is broken to Amit, and he treasures it and cherishes it and tries to figure out how to fix the algorithm," says Matt Cutts, one of Singhal's officemates and the head of Google's efforts to fight Web spam, the term for advertising-filled pages that somehow keep maneuvering to the top of search listings.

Some complaints involve simple flaws that need to be fixed right away. Recently, a search for "French Revolution" returned too many sites about the recent French presidential election campaign -- in which candidates opined on various policy revolutions -- rather than the ouster of King Louis XVI. A search-engine tweak gave more weight to pages with phrases like "French Revolution" rather than pages that simply had both words.

At other times, complaints highlight more complex problems. In 2005, Bill Brougher, a Google product manager, complained that typing the phrase "teak patio Palo Alto" didn't return a local store called the Teak Patio.

So Singhal fired up one of Google's prized and closely guarded internal programs, called Debug, which shows how its computers evaluate each query and each Web page. He discovered that Theteakpatio.com did not show up because Google's formulas were not giving enough importance to links from other sites about Palo Alto.

It was also a clue to a bigger problem: finding local businesses is important to users, but Google often has to rely on only a handful of sites for clues about which businesses are best. Within two months of Brougher's complaint, Singhal's group had written a new mathematical formula to handle queries for hometown shops.

But Singhal often doesn't rush to fix everything he hears about, because each change can affect the rankings of many sites. "You can't just react on the first complaint," he says. "You let things simmer."

The reticent Manber (he declines to give his age), would discuss his search-quality group only in the vaguest of terms. It operates in small teams of engineers. Some, like Singhal's, focus on systems that process queries after users type them in. Others work on features that improve the display of results, like extracting snippets -- the short, descriptive text that gives users a hint about a site's content.

Other members of Manber's team work on what happens before users can even start a search: maintaining a giant index of all the world's Web pages. Google has hundreds of thousands of customized computers scouring the Web to serve that purpose. In its early years, Google built a new index every six to eight weeks. Now it rechecks many pages every few days.

And Google does more than simply build an outsized, digital table of contents for the Web. Instead, it actually makes a copy of the entire Internet -- every word on every page -- that it stores in each of its huge customized data centers so it can comb through the information faster. Google recently developed a new system that can hold far more data and search through it far faster than the company could before.

As Google compiles its index, it calculates a number it calls PageRank for each page it finds. This was the key invention of Google's founders, Page and Sergey Brin. PageRank tallies how many times other sites link to a given page. Sites that are more popular, especially with sites that have high PageRanks themselves, are considered likely to be of higher quality.

Singhal has developed a far more elaborate system for ranking pages, which involves more than 200 types of information, or what Google calls "signals." PageRank is but one signal. Some signals are on Web pages -- like words, links, images and so on. Some are drawn from the history of how pages have changed over time. Some signals are data patterns uncovered in the trillions of searches that Google has handled over the years.

"The data we have is pushing the state of the art," Singhal says. "We see all the links going to a page, how the content is changing on the page over time."

This story has been viewed 0 times.

No comments:

Post a Comment